Festival History: Moving Onto the International Stage

My first job with the festival was working with the international jury in 1986. They awarded the Grand Prize to Wendy Wacko from Jasper, Alberta for her feature-length film The Climb, a dramatic reconstruction of the famous 1953 first ascent of Nanga Parbat by Herman Buyl. The film emphasized the perils of group dynamics, exaggerated in the rarified environment of high, thin air. She later said that winning the Grand Prize in Banff was the highlight of her professional filmmaking career.

Hamish MacInnes, deputy leader of the successful 1975 British Everest Southwest face expedition, was the guest speaker and he regaled the audience with his seriously funny stories of mad rescues in the depths of winter in Northern Scotland.

The marketing background of festival coordinator Denise Lemaster contributed to the growing amount of publicity and awareness the festival was receiving. Headlines like "Fantastic flicks," and "Banff Mountain Festival enters second decade a strong winner,"were complemented by a Media in Adventure seminar featuring some very respected editors: Michael Kennedy from Climbing Magazine, Bruce Patterson from the Calgary Herald, Bart Robinson from Equinox Magazine and George Bracksieck of Rock and Ice. Greater international participation from the Europeans and Asian filmmakers added a cosmopolitan flavour.

One of the beauties of this grass-roots festival was that it evolved in a natural way, always responding to the needs of the community. Each year at the festival, there seemed to be another feature, adding to the richness of the experience. 1987 saw the introduction of the Summit of Excellence Award, which was to be awarded annually to an individual who had made a significant contribution to mountain life in the Canadian Rockies. Over the years, it was to become a much coveted and highly prized award, as it represented recognition by one's peers. That first year it went to Bruno Engler, transplanted Swiss guide, photographer and raconteur, who became a close friend of the festival.

There were other local heroes honoured that year. Sharon Wood and Dwayne Congdon, local residents, members of the "Everest Light Expedition" and Everest summiteers, were the opening night speakers. The audience response was warm and full of pride for these two unassuming mountaineers who had made it onto the international stage, performed well, and survived.

They were in stark contrast to the polished, media-savvy style of another alpine athlete - Christophe Profit, a French climber profiled in Trilogy pour un homme seul. Documenting a daring enchainment-like approach to three formidable north faces in the Alps, with helicopter-assisted descents and television cameras monitoring every move, it was a glimpse of the cutting edge of mountaineering in the Alps at that time.

The festival leadership changed hands in 1988 when I moved to overall Festival Director. My primary goal that first year was to change nothing for fear of interfering with what was obviously a very successful format. But of course, that was impossible — evolution can't be stopped.

There were two new additions to the festival that added depth and personality in very different ways. For the first time, the festival joined forces with the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies to bring a significant mountain exhibition to the valley. It was Galen Rowell's Mountain Light photo exhibit, and it was dazzling! Described by those who saw it as "luminescent," "dramatic," and "stunning," Rowell's imagery gave us all a glimpse of a master at work.

Rowell also opened the festival on Friday night with his impressive presentation on Patagonia, but there was a surprise for the audience that night that really stole the show! Two days prior to the festival the Alpine Club of Canada had hosted the first Canadian Open Climbing Championships and, unbeknownst to the audience, the climbing wall had been set up on stage of the Eric Harvie theatre. As the lights came up and the curtains were drawn for the second half of the program, the crowed was astounded to see two climbers racing their way to the top of the wall in a speed-climbing demonstration.

A tongue-in-cheek reference to this new development in the climbing community read, "Our Brave Mountaineers try the Great Indoors." Reporter Nick Lees went on to describe the scene, "The only hold above was a tiny ledge, barely wide enough to grab...the climber concentrated, reached up and then slowly pulled himself up. The applause in the packed house...was deafening. Applause? Yes folds, a new breed of climber has forsaken the formidable faces of the world and moved the sport to the Great Indoors."

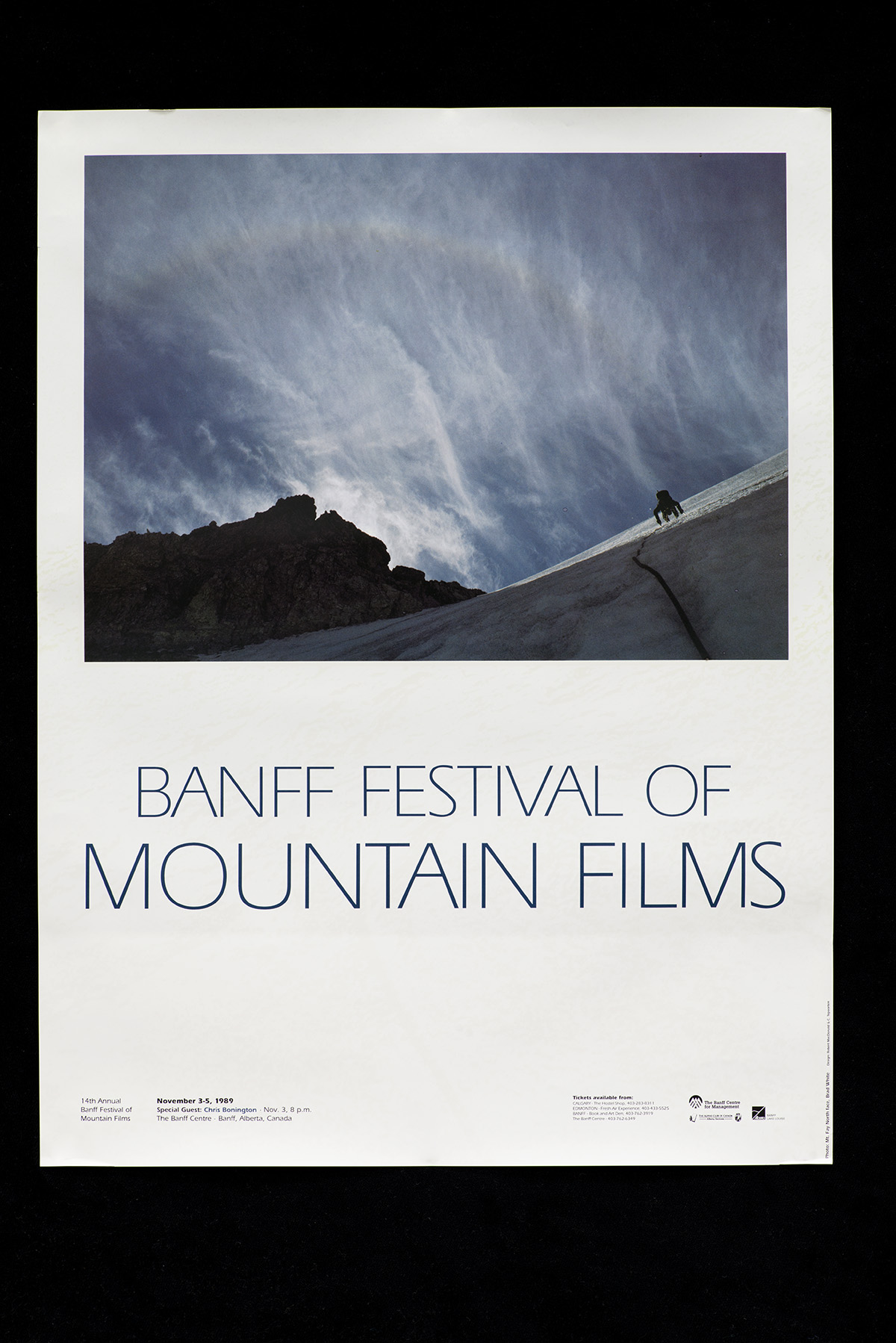

Everyone was thrilled when, in 1989, Chris Bonington opened the festival, mesmerizing the audience as he drew them into one history-making expedition after another.

The international nature of the festival was felt in other ways too. More filmmakers than ever were coming to present their films, meet other filmmakers, exchange ideas, interact with the live audience and see what their competition was doing. Four other mountain film festivals (Telluride, Autrans, Dundee and Annecy) sent their directors to see what Banff was about and search for films for their own festivals.

At this time I began working as a jury member at other mountain film festivals, and this experience was gratifying for several reasons. I had the unusual opportunity to see, first-hand, how other festivals operated, and could take the best ideas from each and incorporate them into Banff. I watched endless hours of film, making it possible for Banff to invite the best films in the world into our competition. And on a personal level, the work would take me to interesting places all around the world, working with filmmakers and professionals in the mountain community.

1989 saw one of the best films ever screened in Banff. Solitary Journey became the festival's first triple prizewinner and nobody who was in the audience during the awards presentation will forget the amazed and emotionally overwhelmed director/producer Suzanne Cook as she repeatedly came to the stage to accept Best Climbing, People's Choice and, finally, the Grand Prize. Solitary Journey was a story of two men, and the mountain that brought them together. Dawa Tenzing, Sherpa guide on the famed 1953 Everest expedition, and Lord John Hunt, leader of that British team related the Everst story from their diametrically opposed East/West points of view. Now in the twilight of their years, both men looked back at their achievement on Everest. Through Dawa's eyes we saw into the hearts of his people who had been changed forever by this historic event.

Technologically, the festival was changing. At the beginning, it was truly a film festival with 16 mm and 35 mm films in the competition. But by 1990, three video formats were also accepted. This presented some very real challenges for the festival as the projection equipment required for video was difficult to find and extremely expensive to rent. But it was a reality and, each year, small advances were made to improve the image.

Even though we were able to keep abreast of the technological changes at the festival in Banff, they were impacting our touring program as well. We had started to get serious about a project that would change the future of the festival in ways we could not predict. In an attempt to bring the film program to more people, we reinstated an earlier initiative of taking a "Best of Banff" program to Canadian communities. The tour quickly grew from three cities to 10 and then...it exploded. It seemed impossible to carry all of that projection equipment around with us, but again, it was a reality and so that is what we did.

The 1990 festival featured another Brit — although a transplanted one. Adrian Burgess, now living in the United States, brought his own ribald brand of humour to the sometimes too-serious side of mountaineering. He was entertaining, informative, and always amusing.

The number of film entries exploded: 140 films from 23 countries made the job of the pre-selection committee take on epic proportions. One film stood out as special: Chasseur de miel was only 20 minutes long, but this French creation by Eric Valli was the predecessor of a filmmaking style we would learn to love. It took an anthropological approach to the brave honey-hunters of Nepal who take life-threatening risks as part of their everyday work, gathering honey off of cliff faces. We were to see Eric Valli's work repeatedly in the years to come, and it was always magical.

As the quality of entries continued to improve and the reputation of the festival continued to grow, so too did the Canadian tour. Except it wasn't just a Canadian tour anymore. With demand from northern U.S. communities, the tour was now up to 38 screenings in 27 cities. That represented a one-year growth of 60% and created a new kind of post-festival life. It was no longer a three-day event, but a month-long "happening." Mountain films were now loved and appreciated from Seattle to Halifax.

The growth of the tour opened up a world of opportunity for the festival — through sponsorship. Now that the festival was reaching tens of thousands rather than thousands of people across North America, it became attractive for corporate sponsors, particularly in the outdoor industry. Their loyal support ushered in a period of financial stability for the festival.

The festival was starting to become comfortable in its position as a leading mountain film festival and was assuming a new and important role as ambassador for the mountain film through its ever-expanding tour.