How This Artist Is Using 3D Video to Connect You to Nature

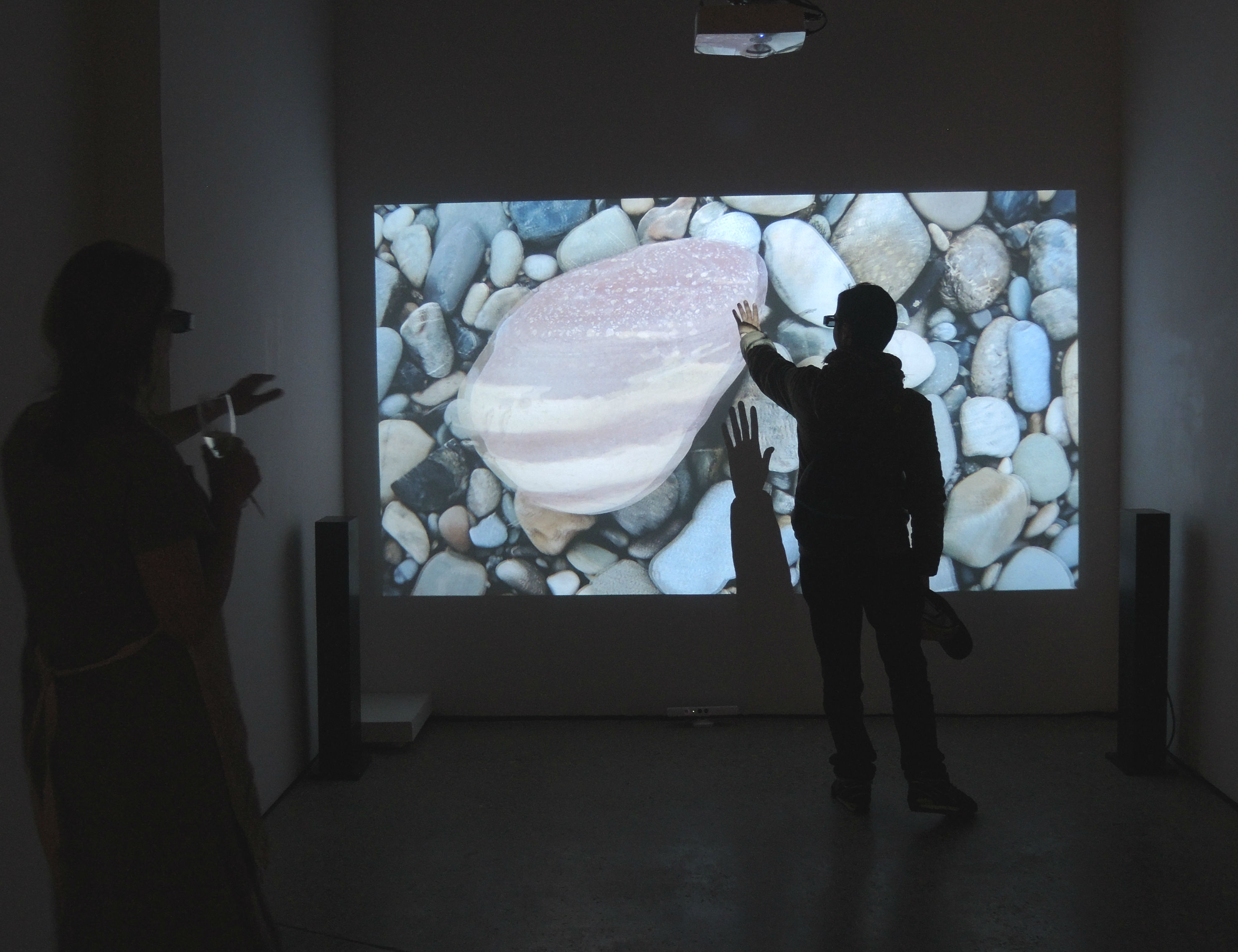

I’m standing in the middle of an empty, echoey gallery space wearing clunky 3D glasses — the kind you get at the movie theatre. Beside me is artist, photographer and documentary filmmaker Marten Berkman. He clicks play on the tiny remote in his hand and the blank wall in front of us surges to life with images of melting snow, a flowing river, and smooth, grey stones.

After a few relaxing minutes listening to the sounds of trickling run-off, the video transitions from spring-like, to summer — fields in full bloom under the shadow of impressive mountains.

“I'm intrigued by how people will sit for three minutes and watch one scene where the only thing that's happening is some blades [of grass] are blowing in the wind,” he says.

He’s right; I’m rapt. But when a shot of a beautiful lake appears, something is off. There are two strange, pixelated shapes standing by the water’s edge — too digital for this natural space.

“That’s us,” he says, sweeping his arm up from his side as I watch the pixel-person mirror his actions. I step forward and so do the particles. I see “my” reflection in the water on the screen.

We’re standing in nature in the middle of a concrete room.

Coming from a background of landscape photography, Berkman knows that human figures are rarely featured in those images, and this puzzled him. To him, there's nothing more intuitive than seeing people in nature.

“If we see ourselves in the landscape, perhaps it is a more accurate reflection of ourselves,” he says. “Because we are not separate from these places.”

And that sense of place is what Berkman hopes to evoke with his work. He’s convinced we all share some kind of ingrained ancient memory of the land, even if we live surrounded by skyscrapers. The built world is also represented in his artwork by interspersed scenes from a metal scrapyard — a jarring shift that reminds us that our desire to create is natural too.

Berkman moved from his hometown of Montreal to the Yukon 25 years ago, and hasn’t looked back. The video footage in his installation, Hart to Heart, was on display in The Project Space at the Walter Phillips Gallery during the 2015 Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival. It was all taken in the Yukon territory’s Peel Watershed, a space currently embroiled in a legal battle over land claim agreements.

“This is really a meditation on that space, a very remote space that most people cannot physically get to,” he says.

Much of Berkman’s work concerns itself with the juxtaposition between the natural world and the built world. Our innate desire to create and develop is as natural as the rivers and mountains, he says. But that need for growth has disconnected many of us from spaces that are inherently part of us.

In presenting the “analog world” in a manufactured space, Berkman hopes people will be reminded of where they came from. He calls this “the ecology of perception”:

“The ecology of perception is about a deepening perception so that we are appreciating landscapes on not only the cognitive level, but the heartfelt level, the intuitive level, the emotive level. If we see the land that way, I think that really opens up to how we treat the land.”

The piece uses stereoscopic video imaging to achieve the 3D effect, something Berkman is intent on using more of in the future after a history of 2D photography and film.

“I so enjoy being able to move around in my own physical space and have that manifest in the virtual space of another geography,” he says.

The 3D nature of his work also allows the viewer to experience the feeling of being there that allows for the emotional reactions Berkman hopes to elicit. When I asked him about the difference between his simulated landscape and an actual river valley, he agreed that nothing beats the real thing. But for those who live in the urban world, the ability to meander through a blooming meadow might not exist.

“I’ve had children write in a book of comments of shows, ‘Thank you so much for letting me stand on that mountaintop that I never would have gone to.’ So they, in fact, have that enthralling experience. Even though it’s virtual, it gave them a taste of something,” he says.

And that glimmer of connection is what so interests Berkman. Watching people watch his piece, he is giddy and interested in their reactions. His love of the great outdoors is what fuels him to make what he calls his life’s work: spreading a passion for nature through art.

“Perhaps this may be a catalyst for people to go and experience it for real,” he says.

It’s a strange feeling watching a video of mountains in a building nestled at the foot of a real one, but I can’t tear myself away. I watch it all the way through. Then I go outside, like Berkman wanted, for a taste of the real thing.