InStudio: The Monster Within

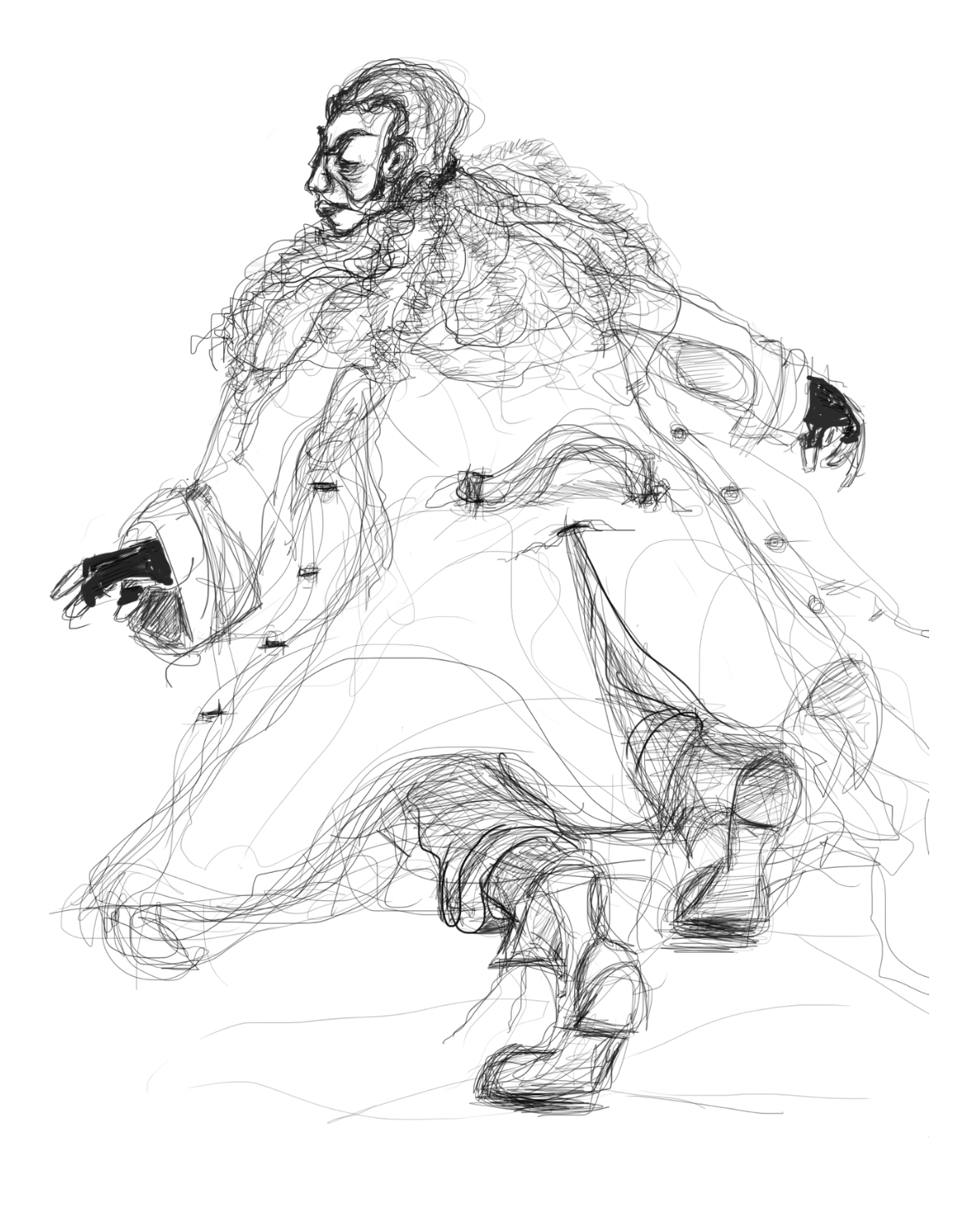

First draft drawing of The Creature by Anne Seguin Poirier for Alberta Ballet's Frankenstein.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the human creature formed and brought to life by the young scientist, Victor Frankenstein, learns to speak and reason fluently. He even reads Milton’s Paradise Lost, and is moved by the epic poem’s depiction of “an omnipotent God warring with his creatures.” Sorrowfully, he compares himself to Adam, who had the good fortune to be “guarded by the special care of his Creator,” and to Satan, with whom he shares “the bitter gall of envy.”

Popular culture tends to ignore the inner consciousness of Shelley’s unnamed and abandoned being, as in the 1931 Hollywood movie of Frankenstein starring the mute and lumbering Boris Karloff. But his complex psychology fascinates Alberta Ballet’s artistic director Jean Grand-Maître, a newly minted member of the Order of Canada known for his “portrait ballets” inspired by the music of Joni Mitchell, k.d. lang and other pop icons.

As he researches his next ballet, based on Shelley’s 1818 science fiction masterpiece, Grand-Maître finds himself impressed by the “utter originality” of this gothic tale, which has accumulated resonance over the 200 years since its first publication, growing to mythic proportions.

“The idea of a human who comes to life in a world without God was truly terrifying in the age of industrialism, and Shelley’s story is even more believable today. Just look at all that’s going on in genetics and with artificial intelligence,” says Grand-Maître. “Some say that Mary Shelley’s scientist and the monster have become one.”

Frankenstein, an ambitious and highly rational man driven to push the bounds of scientific knowledge, suffers pangs of conscience only once it is too late to avoid the death and destruction resulting from his successful experiment to generate life. Transposing his scientific hubris to the present day was key to how Grand-Maître and his design team found a way into the ballet when they met for initial discussions last December.

“We felt that by making our Frankenstein contemporary, people would connect to it in a more profound way than they would as a period piece,” he explains.

Alberta Ballet's director and Order of Canada recipient Jean Grand-Maître.

Their Victor Frankenstein, who will be danced by long-time company member Kelley McKinlay, attends MIT. His ill-fated honeymoon will be set in Whistler. And the finale, which, in the novel, takes place on an 18th-century ship stranded in Arctic ice, unfolds at a meteorological station in Yukon. Cell phones will replace Shelley’s series of letters.

Grand-Maître intends to tackle the actual choreography only once the company is in residence at Banff Centre in July. That’s when Zacharie Dun, cast as the creature, joins him in the studio to find a vocabulary and develop “a real theatrical character.”

Despite being created from a mishmash of body parts, the creature-cum-monster acquires impressive physical prowess. “Mary Shelley describes how he can move like a panther, or run up a mountain or climb an iceberg at incredible speed,” says Grand-Maître. “He’s like a panther that’s been put together with the wrong parts, so there’s going to have to be a spare wheel somewhere in the choreography! I want to evolve the creature’s vernacular from being unable to stand at the beginning of the ballet to a very agile, discombobulated, arrhythmic movement.

At over six feet, Dun is the tallest dancer in the company, helpful in depicting a creature “of a gigantic stature … about eight feet in height,” as Shelley wrote. What really matters, though, goes deeper. “The success in creating this role,” says Grand-Maître, “will be to capture the human trapped in the monster. That being is, at first, good and wants to learn, but because people find his appearance so disturbing, they chase him away and believe he’s dangerous.” The complications of human passion in the face of rejection and loneliness, taken to an extreme, turn the creature into a brutal killer.

“The success in creating this role will be to capture the human trapped in the monster.” - Jean Grand-Maître

While Grand-Maître explores choreography for Frankenstein’s cast of characters, the 12 Alberta Ballet dancers accompanying him to Banff Centre will be busy as well with other company repertoire projects. These involve studio time with Montreal’s Anne Plamondon, who is creating a new piece, and Alberta Ballet’s associate artistic director Christopher Anderson, who is staging Swan Lake.

Members of the company will also contribute to Designing for Dance, a workshop where designers can prototype their ideas on actual dancers, offered as part of Banff Centre’s Creative Gesture program. A dance costume can only be truly seen when it’s viewed in action onstage, explains Montreal designer Liz Vandal, one of two Andrea Brussa Master Artists leading the workshop. Besides animating the costumes for the international mix of designer participants, the dancers will be able to provide practical feedback on how a costume facilitates or hampers their often extreme movement.

Hunkering down at Banff Centre, “so close to the clouds, a sense of family builds,” says Vandal. Being together in this intense artistic climate generates ideas and a collaborative spirit, she says. “To be really creative is like throwing yourself off a cliff, so support is very important.”

Grand-Maître agrees, describing Banff Centre as “a sanctuary, where everything brings you to a place of extreme creativity: you’re surrounded by the beauty of nature and also by creative people. It sparks ideas.”

He looks forward to exploring those ideas, step by step, with his dancers in the studio. Together, they will shape a ballet in which horror arises not from blood on the stage, but from the darkness within.