From Page to Stage: Costume Design for 'The Rape of Lucretia'

We spoke with Camellia Koo, the set and costume designer for the Banff Centre production of Benjamin Britten's The Rape of Lucretia, part of the Opera in the 21st Century residency. Learn more about the program here.

Actors playing soldiers on stage look terrible if you get the details of their costumes wrong—they look, well, costumed instead of authentic.

So while it’s easier than ever to work as a designer remotely, using apps like Pinterest as shared idea boards, Camellia Koo flew from Toronto to work with Banff Centre’s wardrobe team. She wanted to get the details right for Benjamin Britten's The Rape of Lucretia.

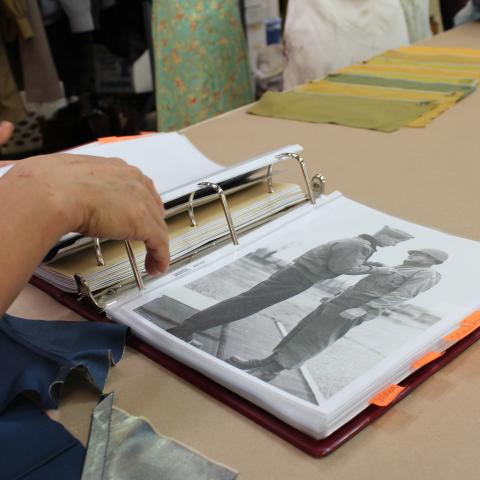

She skipped design sketches because she could more accurately represent details with reference images pinched from Google. Director Paul Curran set the opera, originally set ancient Rome, in the 1940s, so there were plenty available online.

The men’s uniforms were even ordered online, with additional pieces borrowed from Edmonton Opera, found at surplus stores, or pulled from Banff Centre stock.

Though once the costumes arrived, the sewers quickly got to work taking them apart. In order to make it look like the uniform was intended for the particular singer, they treated the costumes as pattern pieces that needed to be pulled apart and put back together.

“I'd call it a three-quarter build, so you pay for it and then you pay for it again,” says Patsy Thomas, head of wardrobe at Banff Centre.

The three ladies in the show are considered “full builds,” with Lucretia’s dress made in three iterations: a mock-up, a clean version with a tear-away sleeve, and a dirty, bloody, ripped version—worn after the rape.

The ladieswear was conceived by looking at reference images and collaging details from different dresses into a mock up. A luxury not all productions get, the mock-up is often made using cheaper material to be used in rehearsal. It’s a good way to get the actor’s silhouette right and to test that the design drapes properly.

At this stage the actors are brought in for a fitting and for questioning.

“They know their character way better than I ever would because they live it every day,” Koo says. So she asks them how they will move on stage and reads them for their level of comfort in the outfit.

This helps prevent the dreaded wardrobe malfunction. If she knows the character is going to do the splits on stage, she’ll have chosen a fabric and fit that will allow for that. She wants the costume to make them feel good, if they think of it at all.

Sitting with the director and head of wardrobe, Koo watches rehearsals to see how the mock-ups are faring. Maybe a hem needs taken down a few inches, or a jacket needs let out. If changes need to be made she reports back to the lead cutter, Judy Darough, who will plan the alterations.

The deadline for final tweaks is opening day, but major changes should happen before the final dress rehearsal so there are no surprises for the performer. Surprises are generally avoided by having a constant dialogue between the costume designer, director, and actor from day one to show close.

“It's just being open and receptive to what the character is supposed to be and who the performer is. I can't impart too much of my own ego in that because then it doesn't leave room for their personalities,” Koo says.

However, The Rape of Lucretia allowed lots of room for her own taste to shine.

There are very few opportunities for brand new productions of opera in North America. Often companies rent older sets and recycle costumes, so Koo jumped on the opportunity to build a show from scratch.

Already there’s buzz about her designs being recycled in remounted productions of this opera. Some interested theatre companies will be attending the opening with the idea of renting components of the show.