Syrus Ware Honours Unknown Activists By Drawing Them 10 Feet Tall

Syrus Ware was drawing another portrait — this one on a much smaller scale than the larger-than-life portraits he is known for — when he noticed something out of the ordinary. His subject was becoming visibly choked up.

Ware normally draws portraits of activists, many virtually unknown outside of the advocate community, but this portrait was more personal.

It was of his father.

“He had been a drill instructor in the marines, and so I did this portrait of him in his uniform,” Ware says. “He was very choked up, because he said ‘no one’s ever made a portrait of me.’”

Drawing this portrait, and seeing the effect it had, reminded Ware, a trans artist based in Toronto, of the story his father had told him throughout his childhood about being asked to join a sit-in in the ‘60s.

“He’s from Memphis, Tennessee, and he grew up in sort of the pre-civil rights era. And there was this moment where these young people came to his high school and asked him to come and get involved in this sit-in at the Walgreens [lunch] counter,” recounts Ware.

At the time, drugstore lunch counters were the equivalent of today’s fast food chains. They were also segregated. Although black people could shop in the stores, they weren’t allowed to stay and eat. This sit-in, and many others like it at the time, challenged that idea.

“And they were like, ‘What you do is you bring your lunch and you sit and you eat and they’ll drag you away. And it’ll be great',” says Ware. “And he decided to not go. He was like, ‘I don’t think so. I can eat my lunch anywhere, I don’t want to go.’”

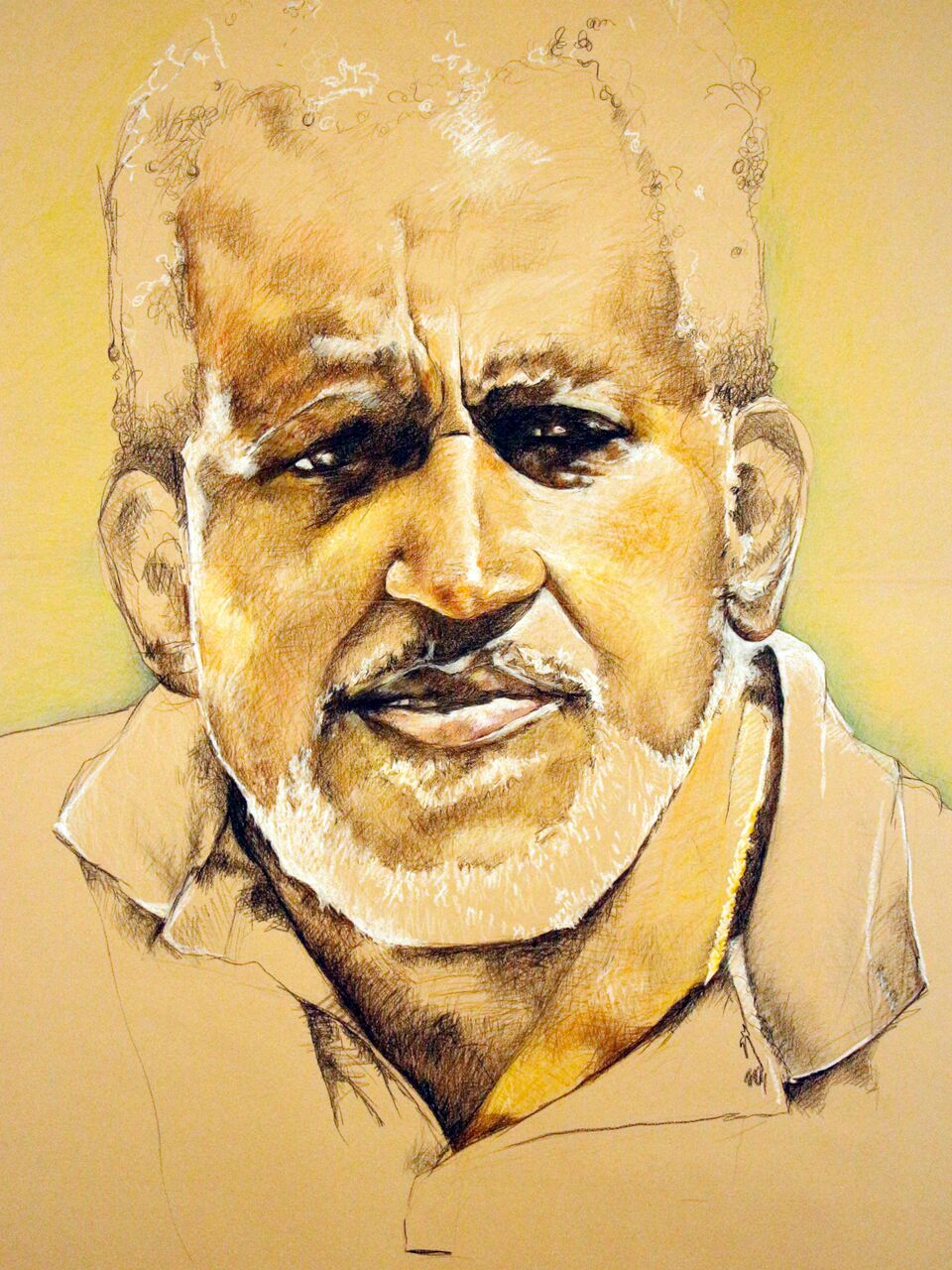

Syrus Ware's father, and the subject of this portrait, became unexpectedly emotional while it was being drawn.

His father’s decision is an important moment for Ware, and it’s one he explores through many of his projects. Ware was at The Banff Centre in 2015 for the Lougheed Leadership program, "Through the Looking Glass," where he explored why people choose to get involved. Although Ware himself is actively involved in organizing movements and demonstrations, his father’s decision not to attend the Walgreens sit-in isn’t something he holds against him. It only makes him more curious about why people choose to become activists.

While he draws his larger-than-life portraits on 10 by 12 foot pieces of paper, Ware asks his subject questions about their work in the community.

“I see it as a way to get to know someone, to spend some time with them,” he says. It’s his own style of research, the findings of which he presents through his art.

These portraits take several days each to complete, which Ware likes to do continuously, pushing his own physical limits. For days at a time, he’ll climb up and down a ladder in order to reach his canvas, slowly bringing the face of his subject into view with each additional line. For Ware, it’s an almost meditative process, giving him plenty of time to really consider their work and what they’ve done. “It’s very intimate,” he says with a laugh.

“For me, this is all about being able to understand what’s happening in your own life. I work in [the Art Gallery of Ontario], and am able to walk through these old masters’ galleries and see there’s just so many amazing, beautiful portraits. But of the usual suspects, right? University chancellors, kings, popes, royalty,” says Ware. His subjects are almost never well-known outside of the activism community. They often include people who became involved because of a particular moment that snowballed into something larger, like supporters of the late Eric Garner and the Black Lives Matter movement.

“There’s something nice about flipping that record and having portraits of unlikely people, drawn with reverence and a scale that really honours the large effect they’re having in my life or in the world.”

Ware realized that his interest in the effect that everyday people can have on a movement stems from the Walgreen’s sit-in story he grew up hearing.

“I’m so interested in that story and that he tells that story. I’m so aware of the way that we rewrite the past. We like to think that we all would go,” notes Ware.

“We all would’ve gone to the sit-in, we all would’ve gone to the march on Washington, all of our relatives helped people in the Underground Railroad. Well, it’s not possible, actually.”

To have joined the Walgreens sit-in “would be really terrifying,” he acknowledges. Many of his family members are still reserved when they talk about their days living in a segregated society.

“There’s a million reasons why he could’ve not gone. But now I haven’t actually asked him in detail about why. I should do that, actually.”

As he grew up and learned more about the civil rights movement, the story Ware’s father told him began to take on a different meaning.

“What are the choices I make?,” Ware asks himself. “When are the times that I choose to go? And when are the times that I choose not to go to the sit-in? What are the things that I’m doing in my daily life? I think [...] a lot of people don’t identify as activists.”

It’s a question — who is an activist? — that Ware asks his audience to consider. It’s one he often asks himself.

“Automatically, I would say I’m at the sit-in,” says Ware. “I’m totally at the sit-in.”