In 1965, when he was 22 years old, David Roberts was part of a team of four who climbed a soaring new route on Alaska’s Mount Huntington, but the achievement was clouded by the death of Ed Bernd during the descent. From this, came David’s first book: Mountain of My Fear. In a fit of catharsis he banged out the tale over nine days during a spring break while working on his Ph.D in English at the University of Denver. The book was acclaimed at the time and remains in print today. The money David earned from its publication led him to become a full-time author.

When David died of cancer at age 78, in August 2021, he had written thirty-two books and dozens of magazine articles. Twenty of those books were about climbing and polar exploration. Ten books concerned his other passion, the ancient and modern history of the Southwestern United States. He also co-authored autobiographical works for climbing legends Ed Viesturs, Conrad Anker, and Alex Honnold. At a particularly bad phase of his illness I suggested he take a breather from writing. “You don’t understand,” he said, “I have to be writing. Without a project I feel I’m wasting time.” Although his last six years were fraught with cancer and its myriad complications, he produced four books.

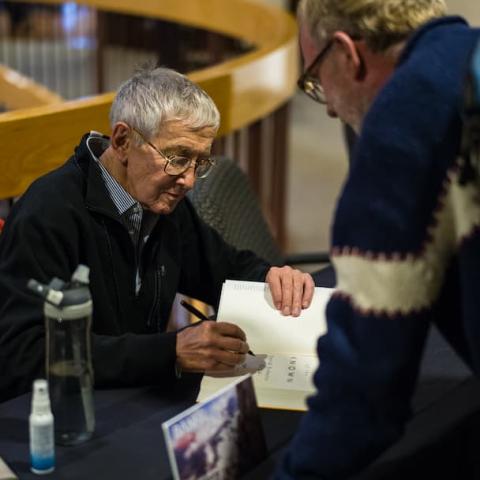

David could research and write a book in a year. He traveled far and wide to peruse libraries and collections. In his home in the Boston region, his bookshelves were crammed with hundreds of volumes on climbing and archaeology. He was a Harvard-graduate gentleman scholar, a Professor of Literature teaching the writing arts at Hampshire College. When visiting the offices of East Coast publishers, magazine editors, and his agent, to pitch a story, he wore a button-down shirt and toted a leather briefcase. He frequented the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival which he loved for its celebration of exploration, and at which his works received accolades. David was one of the few climbers to earn a real living as a writer. His passing marks the end of an era, because, now, such work is ruled by the gig economy.

In the 1960s and 1970s he made thirteen Alaskan mountaineering expeditions when those ranges were wide open for first ascents. In addition to the aforementioned west rib of Mount Huntington, he and his friends pioneered new routes on Shot Tower in the Arrigetch range, the massive Wickersham Wall on Denali, and the 5,000-foot east face of Mount Dickey, to name a few. An attempt to climb Mount Deborah led to his second book, Deborah: A Wilderness Narrative (1970). In that, David crafted a style that would permeate his writing, which was to dissect the inner landscapes of himself and his companions. His partner and tent mate on Deborah was Don Jensen, and David was ruthlessly, uncomfortably honest in describing the traits that irritated each man about the other. Even the sound of Jensen’s breathing was taken to task. Petty? Yes. But honestly, things like that can drive us crazy when we are trapped with our friends in the wild.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the shape of outdoor journalism morphed from staid Explorers Club prose into something like Rolling Stone’s reports from the frontlines of rock ‘n’ roll. Authors became characters in their own stories. Anyone who traveled or climbed with, or even strolled with David was likely to wind up being written about too. Outside Magazine embraced this new wave of reporting, and David became one of their frequent contributors, writing incisive, not-always flattering profiles of climbing stars like Reinhold Messner and John Roskelley.

David felt that a younger generation of climber and explorer cared little for the histories of their sports, perhaps a consequence of too much Instagram and not enough time in libraries. His head was well-stocked with adventure history, as well as poetry and literature. Thus, David’s writing was peppered with the formative elements of climbing, to illustrate the trajectory from hobnail boots and hemp ropes, to soloing El Capitan.

Perhaps David’s strongest suit as a writer was his keen nose for sniffing out bygone survival epics. Some of my personal favorites include Escape from Lucania (2007), about the 1937 first ascent of 17,150-foot Mount Lucania in the Alaska/Yukon wilderness. In this, protagonists Bradford Washburn and Bob Bates become stranded at a remote base camp when the bush pilot cannot return due to the melting of the glacial landing strip. Undaunted, they climb the peak and trek out through uncharted territory and raging rivers to a mining town a hundred miles away.

Another tale rescued from obscurity lies in Four Against the Arctic (2003), about a 1743 shipwreck off the coast of Spitzbergen that leaves four Russians trapped on a tiny island teeming with polar bears. Whenever possible David visited ground zero for his stories, so he and some friends hunkered in a hut on that inhospitable island and dodged polar bears to get a feel for the six years that those men were stranded, during which time they killed nine polar bears with a harpoon, and with bows and arrows made from driftwood.

Also in the category of castaways is Alone On the Ice (2013), which takes a fresh look at the 1913 Australasian Antarctic Expedition led by Douglas Mawson. The action begins with one of the team members plunging to his death in a crevasse, along with a sledge loaded with vital supplies and the dogs hauling it. What ensues is a marathon trek back to base camp across polar ice, more deaths, and a year in a hut during the Antarctic winter in which one man goes mad. All recounted in a sober, analytical style by David.

David thrived on controversial writing subjects. In True Summit (2002), he reexamined the 1950 French mountaineering classic Annapurna, by Maurice Herzog. Perhaps the most famous book about mountaineering, it recounts the French “conquest” of the first 8,000-meter peak. Coming at a time when France was recovering from the humiliation of wartime occupation, its portrayal of courage against adversity (the price of glory on Annapurna was frostbite and amputation) was ripe for the French psyche and it made Herzog a national hero. The other climbers – some of the best in France – saw little recognition, however. David, gaining access to the journals of Herzog’s companions, presented an untold tale of dissent during and after the climb, in which Herzog took the limelight, contractually silencing his comrades from writing their own accounts. With David’s version of this history we are forced to wonder if Herzog’s book, a foundation of our climbing literature, is a fairy tale.

David’s writing often asked why? Again and again he returned to examine the cost-benefit calculus of risk in climbing, and whether the price that many climbers pay – death – is worth it. More than once he concluded that the assumption of risk was justified in order to lead a fulfilled life. But in the books written during his final years, as David confronted his mortality, his writer’s journey arrives at a broader conclusion: that the supremacy of love usurps everything else in life. Proof of this evolution is found in the passages, chapters, and dedications he left to his wife, Sharon Roberts, who stood by him through heaven and hell.

Author: Greg Child