Mountain Fest 1976-80: The High Point on Banff's Cultural Calendar

Looking back over the years of the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival, one cannot but be amazed by how far we have all traveled together. It is a far cry from that cold, blustery day in 1975 when Chic Scott, Evelyn Moorehouse and I sat down on Ev’s basement floor to discuss an afternoon of film entertainment to be sponsored by the Banff Section of The Alpine Club of Canada. Both Chic and I were aware of the Trento Festival of Mountaineering and Exploration Films in Italy, which is the oldest event of its type in the world.

In 1966, I had climbed Nevado Alpamayo in Peru and assisted Ned Kelly in producing his film, The Magnificent Mountain, which later won the prestigious Mario Bello Trophy for mountaineering films at Trento. And Chic had visited Trento while working with Dougal Haston at the International School of Mountaineering in Leysin, Switzerland. Given our location in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, it seemed logical to start a similar festival in Banff, which would become the first in North America. Equally logical was the sponsorship of The Alpine Club of Canada, which has continued to this day.

That one-day event proved to be a greater success than we could ever have dreamed possible. We had planned to use the 250-seat Margaret Greenham Theatre, but an hour before the screenings were to begin found ourselves with an overflow crowd of 450 people struggling to gain admission. Fortunately, we were able to transfer to the larger Eric Harvie Theatre and the four-hour program unfolded without a hitch.

Classics such as Mike Hoover’s Solo, the dramatic Abimes, re-enacting Roberto Sorgato’s dramatic fall on the overhanging North Face of Cima Ouest di Lavaredo in the Dolomites, and the British film Roraima: The Lost World, in which Joe Brown, Don Whillans and Hamish MacInnes slog through slime forest, torrential rain, snakes, scorpions and spiders in order to climb a sheer rock wall in Guyana, kept the audience riveted to the edge of their seats throughout. Many who attended can still recall Joe Brown’s dry comment, “It’s not one of my top 10 favorite hikes,” when asked in the film whether he was enjoying the experience.

Reviewing the Festival in the Banff Crag and Canyon newspaper, local critic Jon Whyte wrote, “I can scarce think of a film orgy that developed in the audience a better communal feeling. If John Amatt can manage to gather a program half as good as this next year, he’ll have to hire security to handle the mobs.” Reflecting back today, it is interesting to note just how close to the truth that predication has become.

The Festival became competitive for the first time in 1977, with a national panel of judges selecting winners from 19 films entered primarily from Britain and Canada. In total, 10 films were screened before an enthusiastic audience of 700 people. The highlights were the Grand Prize winning film, Descent, depicting National Ski Team member Dave Murray training and racing in Europe, and Jon Whyte’s Jimmy Simpson: Mountain Man, a sentimental journey through the memories of one of the early pioneers of the Canadian Rockies. This festival was also notable for the first screenings of the Path of the Paddle canoeing films, marking the start of Bill Mason’s long association as a friend of the Festival.

That first year, our goals were to gather together on an annual basis the best mountain and mountaineering films and to record the sources of such films, so that others might be able to acquire them for later use. Our intent, then as now, was primarily to create an event for the enjoyment of outdoor enthusiasts, but also to provide a platform for adventure filmmakers to showcase their work to the world. At the time, I was heading up the fledgling School of the Environment at Banff Centre – which subsequently was to become part of Banff Centre for Management – and was in the ideal position to undertake the organization of the 1st Annual Banff Festival of Mountaineering Films, which took place on Sunday, October 31, 1976.

The third annual event was noteworthy for two reasons. For the first time, the Festival was expanded to two days and took place over the weekend of November 4 - 5, 1978, thereafter establishing the first weekend in November as the traditional date. And the legendary film producer, F.R. (Budge) Crawley of Ottawa joined us as Chairman of the judging panel, bestowing on us the credibility of his reputation and outstanding achievements in the industry. In 1975, Budge had won an Academy Award in Hollywood for his epic large format documentary, The Man Who Skied Down Everest, which chronicles the frightening descent and fall of the Japanese skier Yuichiro Miura from the South Col of Everest into the Western Cwm. In his opening remarks, Budge talked of the Oscar as being “An American award for a Canadian film about a Japanese skier on a Nepalese mountain,” which neatly paraphrased the international attention that the Festival was receiving.

Outstanding films that year included Bob Godfrey’s Free Climb: The Northwest Face of Half Dome, depicting Jim Erickson’s 12th attempt to make the first clean ascent of this Yosemite classic, and Dudh Kosi: Relentless River of Everest, the Grand Prize winner described as “one of the most exciting whitewater canoe adventure films yet made.” This was the first of many award-winning films that Leo Dickinson would continue to enter, his support being typical to that of many independent filmmakers who would contribute to the event’s success in the early years.

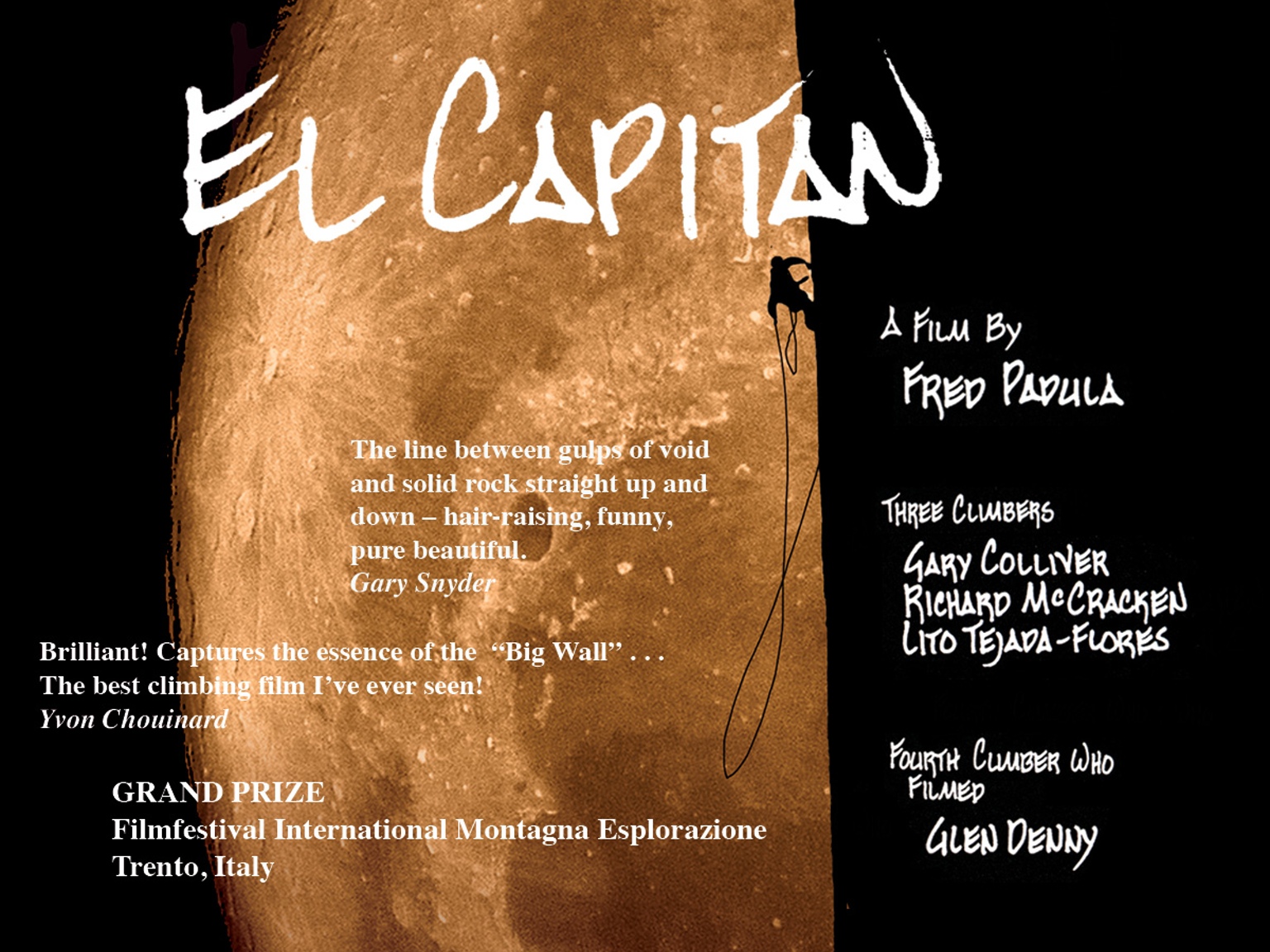

One of the Festival’s most memorable films won the Grand Prize in 1979, the award presented to Fred Padula for his lyrical El Capitan, which depicts a three-day ascent of the 1,000 m. Nose route on this Yosemite Valley landmark. Many who saw this masterpiece can still recall the majestic close-up of the moon as it passed behind the shadowy profile of climbers on the vertical wall. As the jury wrote that year “Amongst climbing films, El Capitan is without peer in poetic beauty.”

There were now 25 films entered from seven countries and a noticeable trend was developing for “adrenaline” films, depicting high-risk sports. The amusing Sky Dive had little to do with mountains, but the audiences loved the freefall parachute jumping and the 3,000-foot plunge off a vertical rock wall in California. Similarly, Fall-Line captured a former surfing champion transferring his skill in one of nature’s most powerful arenas to other areas of challenge, powder skiing and hang-gliding.

El Capitan by Fred Padula

No one really knows what happened during the fifth year in 1980, but it’s fair to say that the Festival exploded. In total, 58 film entries were received from as far away as New Zealand, Japan, Britain, Spain, France, Switzerland, the United States and Canada. For the first time, sell-out crowds flooded the Eric Harvie Theatre and the event was described as “One of Canada’s most unique movie events,” and “The high point on Banff’s cultural calendar.”

One of the best mountain feature films ever made, Mort d’un Guide, won the Grand Prize. This epic suspense-filled drama tells the story of two guides who attempt to regain their reputations by making a new route on the West Face of the Dru, near Chamonix, France. One guide dies and the other is rescued, only to return later in an attempt to finish the climb. And in the Mountain Sports category, Once in a Lifetime: The Underground Eiger captured everyone with its footage of cave divers exploring the world’s longest known underground river in England.

From the overwhelming response of festival audiences and independent filmmakers alike, it was evident that the Banff Mountain Film Festival had now assumed a place as one of the leading adventure film festivals in the world.

“The High Point on Banff’s Cultural Calendar” by John Amatt is an excerpt from the book Voices From the Summit, published in 2000 by National Geographic and Banff Centre.