Parliament's New Poet Laureate on Why Parliament Even Needs a Poet Laureate

George Elliott Clarke has spent the past three years fighting for a place at the podium. Now he’s going to make sure he hangs on to it.

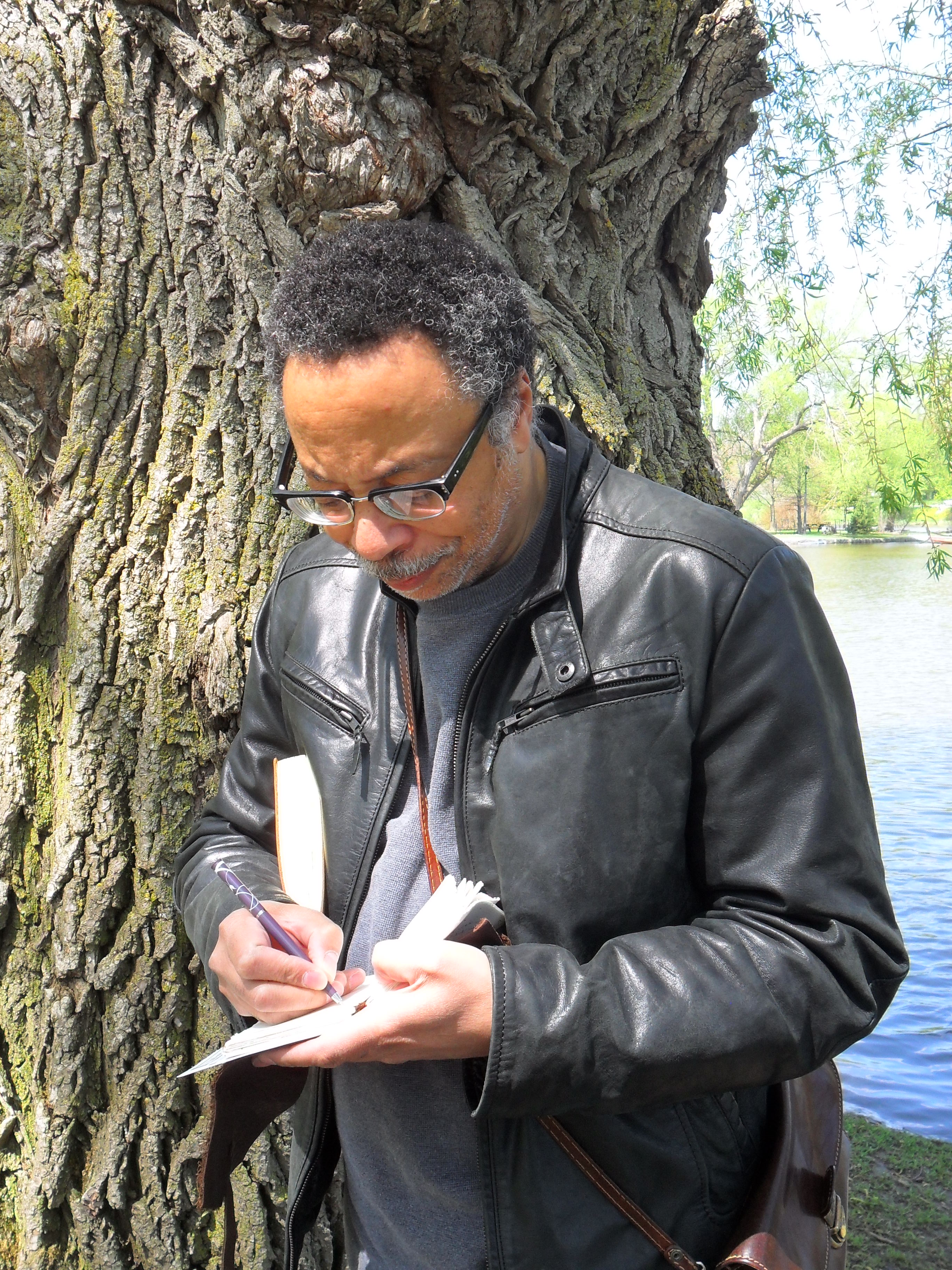

The 56-year-old has just been picked as Canada’s seventh parliamentary poet laureate. Traditionally, not a real high-profile job — most Canadians are probably only aware the post exists every two years, when a new one is announced.

But Clarke doesn’t plan to spend his time crafting verses to be filed away and forgotten. In his eyes, this isn’t a ceremonial position; Parliament needs a poet laureate to underscore why it exists at all.

“One of my jobs is to remind parliamentarians and citizens that Parliament has a duty to use language … to uplift society,” he says.

“It’s impossible to sever the very tight connection between language and law. To have a just or equal society, you must have respect for the power of words.”

That’s not how the role has always been seen. When governments in Canada started appointing poets laureate decades ago, he says, it was kind of like buying a painting to hang on the wall: nice to have, but ultimately just decoration.

The Nova Scotia-born poet ran into that attitude in 2013, when he was chosen as Toronto’s poet laureate. Officials were glad to have him on-board, but weren’t clear on what exactly they wanted him to do.

“There was confusion. A lack of attention, lack of focus. Part of my mandate in Toronto was to say “this is what I can do, this is what I should do.”

He was expected to create legacy projects for the city, but had no budget to do so. Clarke says it was even a struggle to allow him to perform his poetry at special events in the city. He had to convince officials that he needed to be the one behind the podium, that a poem can mark a memorable occasion in a way no politician's speech can.

“We can recognize the magic of an occasion using magical words, “ he says.

“Make that moment rise above its occasion.”

Even more, he sees the post as a way to convince politicians of the importance of oration — a reminder of the way speakers like John Diefenbaker, Winston Churchill and Martin Luther King used to be able to capture attention with a few well-placed words.

It’s a lesson, he argues, desperately needed in the “era of the soundbite,” where nuance is often traded in for a chance to attack opponents.

The new role will be a change for Clarke. A celebrated-poet and playwright, his work has explored themes of crime and justice in Canada. Much of his work focuses on race and history of black communities in Atlantic Canada — such as the opera Beatrice Chancy, for which Clarke wrote the libretto while at Banff Centre in 1993. (Clarke most recently visited the centre in 2014 for a spoken word workshop. While there, he spoke with Mojo Anderson on Writer's Range.)

He’s been vocal politically, and has not been shy about criticizing governments in the past.

But as the poet laureate, he says he’s been appointed to work for all parliamentarians — not just those whose views align with his.

“What I will not do, can not do, is indicate the angels and the devils,“ Clarke says.

Clarke’s two-year term will be marked by a some monumental anniversaries: 100 years since the Halifax Explosion, the centennial of women’s suffrage and, of course, 150 years of Confederation. Aside from marking the country’s memorable events, Clarke says he is planning several major projects. The first will be a poetry map, highlighting the work of an artist from every one of Canada’s political ridings.

“[It will be] posting poems that are important. Not what professors or literary critics think are important, but that the people in that constituency thing are important,” he says.

He also hopes to work with the Library of Parliament to make its archives more open to the public. But ultimately, Clarke sees his goal as making the poet laureate an indispensable part of parliament. And to pave the way for the person who takes the job after him.

“I’m responsible to poet laureate number eight, so that he or she has something to step into.”

During George Elliott Clarke’s visit to Banff Centre in 2014, he spoke with Writer's Range podcast host Mojo Anderson: