Artist Lou Sheppard Finds Beauty in Between Spaces

Lou Sheppard, 2017's Emerging Atlantic Artist, soldering materials at Banff Centre.

Lou Sheppard is the second annual winner of the Emerging Atlantic Canada Artist award. We caught up with them during their eight-week fully funded residency at Banff Centre.

In Lou Sheppard’s sunny Glyde Hall studio, it’s hard to focus on just one thing. The visual artist has so many projects, so many ideas, and they’ve all exploded onto the walls and surfaces, making it near-impossible to stop swivelling my head to look at every tiny detail.

“My way of working is having a bunch of stuff on the go,” says Sheppard, a Halifax-based creator and educator.

To the left is a collection of information and diagrams about sea ice and the polar ice caps; data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center updates live on the monitor. To the right, a series of laser-cut waveforms of birdsong—an owl’s, a raven’s. Straight ahead is a blinking display of LED-illuminated emoji icons around the phrase “We’re going to be fine.”

At first glance, nothing seems to connect, but the thread through Sheppard’s work is more journey than destination. “My practice comes from more of defining a process and the result is more incidental, I think,” says Sheppard.

“Within that incidental nature, there’s a lot of potential for surprise and, I think, a kind of beauty.”

Sheppard is the winner of the 2017 Emerging Atlantic Canada Artist award, given annually in recognition of an East Coast artist’s emerging and exciting practice. The award includes an eight-week residency at Banff Centre, and a speaking tour to discuss some of the work completed while in residency. The award is an an initiative of the Hnatyshyn Foundation focusing on supporting communities in Atlantic Canada, funded with the generous support of the Harrison McCain Foundation and administered by Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity.

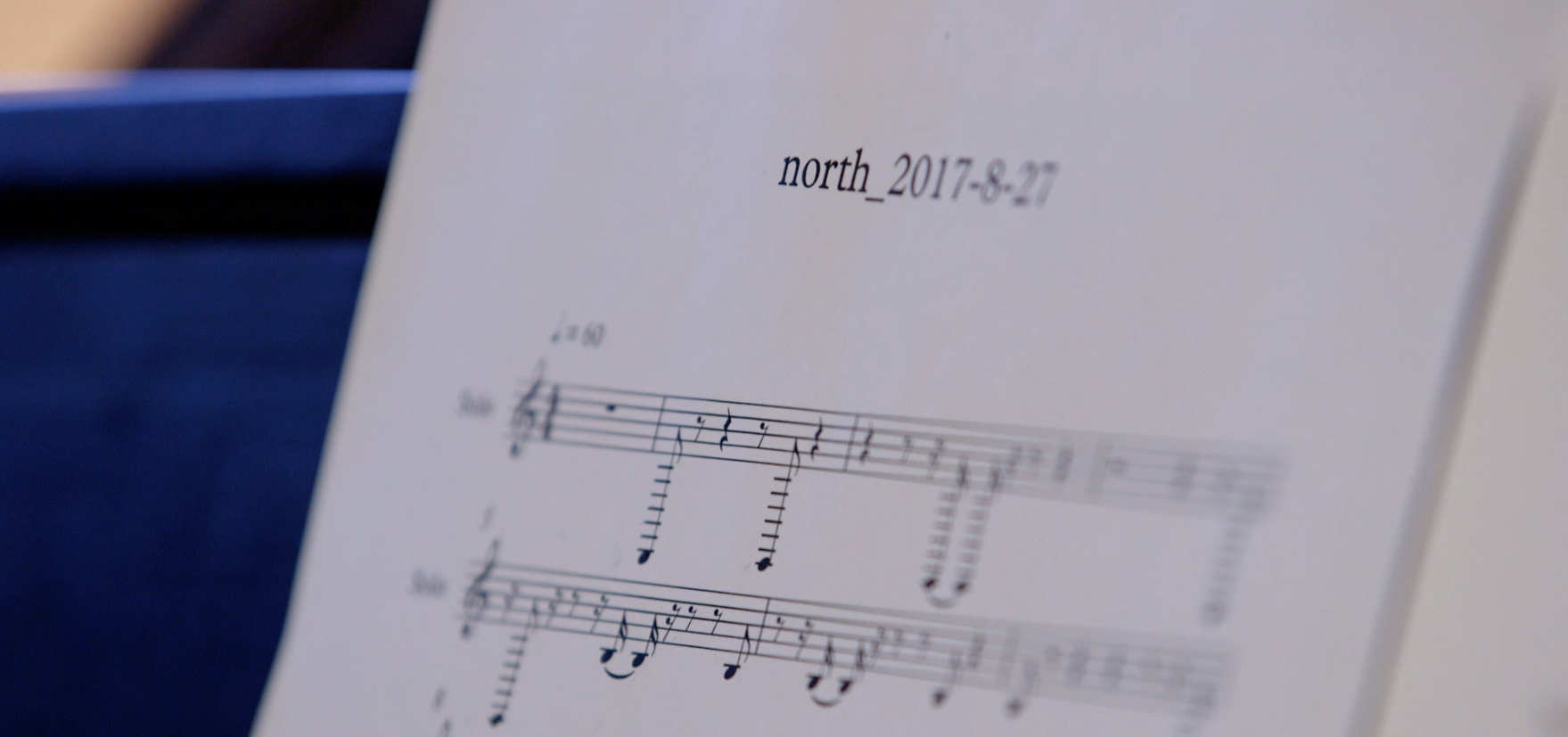

One of the two daily scores generated by Lou's program, which assigns musical notes to the size, shape, and density of the two polar ice caps.

Sheppard’s major project at Banff was a sonification of data about the two polar ice caps. Sheppard worked with Banff Centre’s Kenny Lozowski to develop a computer program which turned hard data about Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets into musical scores—from ice sheets, to sheet music.

Sheppard and Lozowski’s program plots points around the two ice masses daily, as the shape and density of the masses shift. Those points are then translated into notes—the closer together two plot points, the faster the music is played. Similarly, the thicker the ice in that spot, the louder the note is to be played.

The result is two new musical scores daily that, when played, sound abstract, and challenging to listen to. Players are illuminated by lights that Sheppard created that brighten or dim based on the amount of light the ice is reflecting that day—the brighter the lights, the more light being reflected, and thus less light is aimed directly into the ocean, ultimately warming it.

The working title of the piece is Requiem for the Polar Regions, related to Sheppard’s earlier piece, Requiem for the Antarctic Coast, part of the first Antarctic Biennale.

“The idea of requiem...it’s a bit of a funeral. But it’s also a kind of witnessing, or recognizing,” says Sheppard. “I think it’s interesting to think of it that way.”

Even more interesting, perhaps, is the fact that Sheppard wouldn’t be able to play the scores themself. Neither a musician, nor a statistician, nor a programmer, for Sheppard, the interest lies in the translation between those systems.

“There’s space within those translations for failure, or potential new meaning,” says the artist. “It almost becomes a space of metaphor and possibility. That’s why I like moving between systems. Especially with the data to music...it’s two systems I don’t really understand.”

But coming from a place of curiosity to explore a concept that many don’t understand makes the work all the more relatable.

Says Sheppard, “I’m trying to give people other ways of understanding and other ways of thinking about climate.”

Being able to attend Banff Centre and work with those who do understand both data and music was key to Sheppard’s success, they said. “It’s kind of overwhelming to see all of this coming together, and people being engaged with it. I think there’s a real genuine interest in art and art practice here. It’s not always this way and it’s certainly not this way in the regular world.”

But as an artist from Atlantic Canada, Sheppard’s world in Halifax is more supportive than most; East Coast artists, says Sheppard, share something special.

“The spirit of Halifax is just making these strange little spaces that are our own because we don’t necessarily have larger, bigger, shinier things. It’s a bit scrappy and special in that way.”